How we teach composition is shifting in the digital age, a revolutionary period in human communication wherein billions of people carry portable mass-media devices that can send messages of any length and type to all corners of the globe.

In “The Digital Imperative: Making the Case for a 21st Century Pedagogy,”1 J. Elizabeth Clark throws down an eloquent challenge to the Academy. She says we should “articulate how technology is radically transforming our understanding of authors and authority and to create powerful new practices….”2 Yet academia, she notes, has been slow to teach “these new habits of thought.” Traditional essay literacy still dominates composition classrooms, Clark points out, and “needs to be replaced by … digital rhetoric … that engages students.”3

Clark is right. Her argument underscores the need for composition instructors across the land—those already trying new practices as well as the rest—to engage in conversation about how we incorporate digital and media literacy in our teaching of freshman composition. This, while holding on to the basics: thesis statements, summary and analysis, grammar and punctuation, paragraph development, and generally, clear expression.

Perhaps if those of us who teach composition were to see the new digital world as a logical evolution of what came before, change would come more quickly. This essay lays out the limits of the traditional rhetorical triangle, sometimes called the communications triangle, as a theoretical basis for teaching composition (or any form of communication). An alternative, more apt basis in the digital age, I propose, is the rhetorical tetrahedron.

* * *

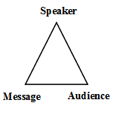

More than two thousand years ago, Aristotle defined rhetoric as “the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion.”4 His famous three appeals of rhetorical persuasion, Logos (logic), Pathos (emotion), and Ethos (character) have been used ever since to define rhetorical quality. His dissection of the elements of an act of communication included the basic elements of speaker, message, and audience, though he didn’t attach those to any emblematic geometry.

In 1971, American scholar James L. Kinneavy gave shape to those ideas. In A Theory of Discourse, he wrote, “Basic to all uses of language are a person who encodes a message, the signal (language) which carries the message, the reality to which the message refers, and the decoder (receiver of the message.)”5 To illustrate his theory, Kinneavy chose the triangle.

Since then, the “rhetorical triangle” has been the theoretical model behind the way we teach composition. Scholars from different fields use different terms, producing numerous interpretations. Some scholars layered Aristotle over the triangle, with the three points being

- Ethos – the speaker or encoder of the information

- Logos – the message, text, linguistic product, signal

- Pathos – the audience, receiver, decoder

Kinneavy’s fourth element, “the reality to which the message refers,” was also called “context,” or “purpose,” and more or less floated in and around the triangle.

Figure 1. A traditional rhetorical triangle

More than earlier linear models of communication,6 the triangular shape effectively captured the interrelationships between the elements: speakers have relationships with their messages, with their audiences, and with the larger context beyond. Each of those elements, in fact, have relationships with one another. An audience, for example, may choose to believe or reject a message, depending upon its view of the speaker, the message itself, or even its perception of the larger realities, the context.

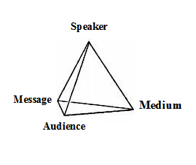

As useful as the triangle has been, the digital revolution has added a new dimension to the model: medium.

More than a half century ago, the eminent media scholar Marshall McLuhan predicted7 that communications technology would continue to evolve and that we would evolve along with it. Why are our evolutions linked? Because, McLuhan argued, communications media don’t just put a picture of the world into each of our heads; they give us the means to extend our minds back into that world.

In Understanding Media, McLuhan said “[T]he personal and social consequence of any medium—that is, of any extension of ourselves—result from the new scale that is introduced into our affairs by each extension of ourselves, or by any new technology.”8 Just one piece of technology, the lowly electric light, could allow us to do everything from performing brain surgery to playing baseball at night. As McLuhan wrote:

It could be argued that these activities are in some way the “content” of the electric light, since they would not exist without the electric light. This fact merely underlines the point that “the medium is the message” because it is the medium that shapes and controls the scale and form of human association and action.9

McLuhan’s insight was profound, revolutionary. There is something more than a speaker shaping a message. There is the medium itself. This notion took some thinking to understand in the early days of electronic news. Without the technology to enable it, we would not have seen the photograph of the earth hanging in space that helped propel the global environmental movement. Today, we receive weather news, traffic reports, up-to-the-minute stock prices, even pictures from the planet Mars, not from human beings, but from robotic correspondents. On behalf of its programmers, the medium actually produces the message. Digital media, more than any medium before, shape and control “the scale and form of human association and action.”10

Messages assembled by non-human speakers are increasing. “ChatBots” simulate public conversations with real people. Those computer programs flourish because they interact. Engagement, in fact, is a distinguishing characteristic of the digital age. The one-way mass media models of the twentieth century—newspapers, magazines, radio and television—have been disrupted by the transformation of what we once called “audience.” These days, audience has become a community capable of tweeting, posting, blogging, of talking back to the speaker—in effect, becoming its own army of new speakers.

Old institutions are challenged by what is new. The digital age needs its own laws and regulations, its own ethics and best practices, and yes, its own philosophy, its own theory.

Champions of the traditional rhetorical triangle never anticipated a buzzing, bustling web of rhetorical exchanges. In an era when a message can be an image, a sound, a video, a graphic, or a piece of text, the old two-dimensional model now appears inadequate. Consider the scope of modern networked communication described by Cornell University computer scientist Jon Kleinberg:11

Much of the information that flows through a social network radiates outward in many directions at once. A rumor, a political message, or a link to an online video—these are all examples of information that can spread from person to person, contagiously, in the style of an epidemic. This is an important process to understand because it is part of a broader pattern by which people influence one another over longer periods of time, whether in online or offline settings, to form new political and social beliefs, adopt new technologies, and change personal behavior.12

Whatever this is, it is not a triangle.

* * *

Before the personal computer, World Wide Web, or smart phone, Kinneavy emphasized that the foundation of sound communications theory “must be grounded in the very nature of the language process itself.”13 Just as all uses of language involve speaker, message, receiver, and contextual reality, they also involve media, and always have. In Aristotle’s day, it was the spoken word. Now, it can just as easily be digital.

The rhetorical triangle has been adopted by communicationists (as Kinneavy describes it) as “central to their discipline”14—a reflection, he notes, of Harold D. Lasswell’s basic formulation: “Who says what to whom and why?” But turn that flat triangle into a tetrahedron, and the question becomes: “Who says what to whom, how, and why?”

How do media rise to the level of the axiomatic? Never mind that speed is unprecedented; that volume is virtually endless; that digital media, unlike other forms of communication, can be broad and deep. There is something bigger than all that. Taken together, digital media seem to resemble a giant human brain, uncountable numbers of electrons shooting around the planet, synapses firing every second, different parts of the neural network “lighting up” at any given moment. Taking McLuhan at face value, the ultimate digital technologies will produce the ultimate extension of the human mind, both individually and collectively.

Such a system represents what R. Buckminster Fuller, the American architect and systems theorist, would call “synergistic,” meaning its behavior as a whole is unpredicted by (and greater than) the behavior of its individual parts. In Synergetics: Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking,15 Fuller argued, “thought is systemic … all systems are polyhedral.” Fuller never singled out rhetoric or communication, yet since they are also systems, a single act of communication could be represented by the simplest polyhedral form: the tetrahedron.16

Figure 2. A rhetorical tetrahedron, or communications tetrahedron

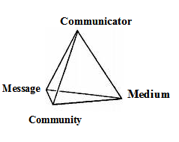

A tetrahedron reflects a digital world that is multi-nodal; any message in the network can affect not only those immediately involved but also the entire network. In addition, this is why “audience” is no longer simply the receiver of the message but also the potential generator of myriad new messages. Once a message finds its way into a three-dimensional, multi-nodal network, its meaning can change. What begins as a love note can end a political scandal. Of course, this has always been a possibility. But the digital age has so amplified the process that echoes of a message can, in a flash, render the original obsolete. So we must further update the tetrahedron, changing “speaker” to “communicator,” and “audience” to “community.”

Figure 3. The final version of the rhetorical tetrahedron

* * *

Just as McLuhan merged media and message, interactive media are merging community and communicator. In ways not fully understood, the digital community’s vast numbers of sub-communities can take a message and explode it into a constellation of new messages. Tetrahedrons are useful for showing how messages flow through networks. Since they are the simplest solid structures in nature, virtually any other shape can be created with them. The nodes of the tetrahedrons connect to other tetrahedrons. A message hits a community, which creates new messages, which create new structures of communication.

Each step along the interactive communications path, each re-framing through a new medium, becomes its own unit of communication. But that unit of communication is inextricably interconnected to others—dozens, possibly thousands.

Once we figure out how to map the tetra-built forms, we may discover a news story (or a composition essay) that look like fig. 4:

Figure 4. A tetra-built form

Much more needs to be known, particularly about why some messages are “sticky,” i.e., make their way easily around the network, and why some individuals become “nodes,” i.e., agents of more frequent creation and distribution.

In the years between my first writings on the rhetorical tetrahedron in 2009 and my blog post describing it in 2012,17 I realized that, like the triangle before it, the tetrahedron will be the subject of numerous interpretations. Indeed, in January 2014, Clemson professor Sean Morey published The New Media Writer, a multimedia “electrate text,”18 in which he describes a fourth side to the structure as “Kairos” (literally, the right time), and to that new side he adds the concepts of design, genre, and medium. If the tetrahedron catches on, many more interpretations will no doubt surface. No matter what the variant, the point remains: we have outgrown the triangle.

This is especially important in light of the emerging communication behaviors of the young. Writes Bronwyn Williams,19 “Interactive media have created not only the opportunity to appropriate texts and reconstruct them but also the confidence and expectation within students to take such control….”20

* * *

The students we teach comprise the population Marc Prensky calls “digital natives”21—young people who have grown up in a wholly wired world, who, unlike other generations, “are used to receiving information really fast… [who] like to parallel process and multi-task… [who] prefer their graphics before their text rather than the opposite… [who] function best when networked.”22

My own two digital native sons get their news via social media and text messages and create, use, and send it the same way. When something big happens (Bin Laden is dead), they hear of it as quickly as anyone. Sometimes more so. They have arranged their networks, and their position within them, so news finds them fast. They seem better informed than my generation was at their age.

They live in a world of nearly infinite interconnecting rhetorical tetrahedrons, a network symbolizing humanity’s ever-more-complex development.

This new paradigm is useful for teaching Rhetoric and Composition. To meet Clark’s “digital imperative,” however, we must continue to explore and develop a teaching philosophy “aimed at furthering students’ digital literacy.”23

Some instructors and colleges are already doing just that, in myriad innovative ways:

- At Florida State University, The Digital Studio helps students “understand and put into practice the connections between digital composing tools and rhetoric, a connection that also assists in helping students see common ground between composing alphabetic texts and multimodal texts.” The studio professors describe their goal as inspiring “questions about best practices for employing digital tools for pedagogical purposes. In particular: what are effective approaches to teaching composing with digital tools that extend beyond mere ‘skills training’ and can challenge teachers and students to be critical and rhetorically savvy users of digital software?”24

- At Arizona State University, a group of instructors was given the task of upending freshman composition to account for the university’s ever-growing number of online students. The program’s instructors explain, “We revised writing assignments that encouraged the development of multimodal composition. We aimed to help students understand that authors develop texts in response to a rhetorical situation for a specific audience and purpose, as opposed to defaulting to essay production for teacher as audience. The projects that students produced included, but were not limited to, blogs, videos, websites, sound portraits, newsletters, advertisements, and articles both for print and online forums.”25

- At Michigan State University, the WIDE Research Center Collective explores and develops “technology-rich instructional space[s] for teaching writing in a collaborative, interactive, digitally enhanced environment.” In “Why Teach Digital Writing?” the center’s professors say composing documents with multiple media, publishing quickly to mass audiences, and allowing interaction with the writing and writers “[challenge] many of the traditional principles and practices of composition, which are based (implicitly) on a print view of writing.… This change requires a large-scale shift in the rhetorical situations that we ask students to write within, the audiences we ask them to write for, the products that they produce, and the purposes of their writing.”26

But composition instructors need not have the major resources or institutional underpinning of a center to change with the times. Modest examples from my own experiences:

- Pop quiz: Students receive a handout with 10 questions such as, how high is the Empire State Building, who are Florida’s Congressmen, or who wrote Walden. After a few minutes of mass grumbling, they are asked to get with a partner, take out their phones, and work together to search the Web for the answers. The first pair to get them all wins. As soon as they start searching, the classroom bustles with activity. Students discover that they have not only the Empire State Building but also the world at their fingertips.

- Presentations: Students create pre-essay presentations in front of the class on the big screen using mostly images, along with short quotes and summary, to visually reflect a text we are studying.

- Social media: Students are offered up Walt Whitman’s line, “The powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse.”27 They then “contribute a verse” to the global conversation by posting something they have done for class—a paragraph, photo, even a line—to the social medium of their choice.

- Speed Dating: Students are given a list of ungrammatical sentences, bad thesis statements, and terms to define. They then work in pairs on the first item on their list. At the sound of the buzzer, they move on to the next person, and then the next, and work on a new problem. This recreates a network in which everyone communicates and collaborates with everyone else.

All of the above examples, the large and the small, have common elements. They are attempts to embrace Clark’s “digital imperative.” They see composition, in today’s “maker” culture, as an open, collaborative, multimedia endeavor. They encourage students, at least some of the time, to create publicly, with the professor as a guide, in the same way nascent drivers travel public roads, instructors by their sides. As Clark notes, these ideas have not yet swept through all the classrooms where composition is taught.

A different way of seeing things might quicken the pace. By turning the rhetorical triangle into a tetrahedron, by adding “medium” to message, by viewing audience as “a community of communicators,” we would align theory with practice. By taking McCluhan beyond mass media to all rhetoric, by elevating “mesos”—Greek for medium—to the level of logos, pathos, and ethos, we would acknowledge that the digital age is indeed a new era of human communication. The rhetorical tetrahedron offers a new visual representation that could help further the discussion.

Bibliography

Clark, Elizabeth J. “The Digital Imperative: Making the Case for a 21st-Century Pedagogy.” Computers and Composition 27, no. 1 (2010): 27-35.

Fuller, R. Buckminster. Synergetics: Explanations in the Geometry of Thinking. New York: Macmillan, 1975.

Hart-Davidson, Bill, Ellen Cushman, Jeff Grabill, Dànielle Nicole DeVoss, and Jim Porter. “Why Teach Digital Writing?” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy 10, no. 1 (2005). http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/10.1/coverweb/wide/.

Hogan, Mary Ann. “Rhetorical Polyhedra Redux.” Joe’s Barks and Bites (blog). October 6, 2012. http://joejoesbarksandbites.wordpress.com/2012/10/06/rhetorical-polyhedra-redux/.

Kinneavy, James L. A Theory of Discourse. New York: Norton, 1971.

Kleinberg, Jon. “The Convergence of Social and Technological Networks.” Communications of the ACM 51, no. 11 (November 2008): 66-72.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extension of Man. Edited by W. Terrence Gordon. Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press, 2003.

Mehler, Josh, Stephen McElroy, and Jennifer Wells. “Procedures, Projects, and Programs: Florida State University’s Digital Studio Handbook.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy 19, no. 2 (2015). http://praxis.technorhetoric.net/tiki-index.php?page=PraxisWiki%3A_%3AProcedures_Projects_Programs.

Morey, Sean. The New Media Writer. Southlake, TX: Fountainhead Press, 2014.

Prensky, Mark. “Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants.” One the Horizon 9, no. 5 (October 2001): 1-6.

Rankins-Robertson, Sherry, Tiffany Bourelle, Andrew Bourelle, and David Fisher. “Multimodal Instruction: Pedagogy and Practice for Enhancing Multimodal Composition.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy 19, no. 1 (2014). http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/19.1/praxis/robertson-et-al/.

Ross, W.D., ed. Ars Rhetorica. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959.

Weaver, Warren, and Claude Elwood Shannon. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. 1963.

Whitman, Walt. “O Me! O Life!” Walt Whitman: Complete Poetry and Collected Prose. Edited by Justin Kaplan. New York: The Library of America, 1982.

Williams, Bronwyn. “What South Park Character Are You? Popular Culture, Literacy, and Online Performances of Identity.” Computers and Composition 25, no. 1 (2008): 24-39.

- Elizabeth J. Clark, “The Digital Imperative: Making the Case for a 21st-Century Pedagogy,” Computers and Composition 27, no. 1 (2010): 27-35.↵

- Clark, The Digital Imperative, 27.↵

- Ibid., 28.↵

- W.D. Ross, ed., Ars Rhetorica (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959), 6.↵

- James L. Kinneavy, A Theory of Discourse (New York: Norton, 1971), 20.↵

- Warren Weaver and Claude Elwood Shannon. The Mathematical Theory of Communication (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. 1963). In “Fifty Years of Shannon Theory,” Princeton’s Sergio Verdu called Shannon’s seminal 1948 work “the Magna Carta of the information age. He described its dissection of the technical aspects of electronic communication (information, source, transmitter, signal—affected by noise—receiver, destination) as “a unifying theory with profound intersections with Probability, Statistics, Computer Science and other fields.” Verdu, Sergio, “Fifty Years of Shannon Theory,” IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 44, no. 6 (October 1998): 2057.↵

- Marshall McLuhan. Understanding Media: The Extension of Man. ed. W. Terrence Gordon (Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press, 2003), 18-20.↵

- McLuhan. Understanding Media, 19.↵

- Ibid., 20.↵

- Ibid.↵

- Jon Kleinberg, “The Convergence of Social and Technological Networks,” Communications of the ACM 51, no. 11 (November 2008): 66-72.↵

- Kleinberg, Convergence, 70.↵

- Kinneavy, A Theory of Discourse, 18.↵

- Ibid., 19.↵

- R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics: Explanations in the Geometry of Thinking (New York: Macmillan, 1975), 95-97.↵

- Fuller, Synergetics, 96.↵

- Mary Ann Hogan, “Rhetorical Polyhedra Redux,” Joe’s Barks and Bites (blog), October 6, 2012. http://joejoesbarksandbites.wordpress.com/2012/10/06/rhetorical-polyhedra-redux/.↵

- Sean Morey, The New Media Writer (Southlake, TX: Fountainhead Press, 2014).↵

- Bronwyn Williams, “What South Park Character Are You? Popular Culture, Literacy, and Online Performances of Identity,” Computers and Composition 25, no. 1 (2008): 24-39.↵

- Williams, 29.↵

- Mark Prensky, “Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants,” One the Horizon 9, no. 5 (October 2001): 1-6.↵

- Prensky, Digital Natives, 2.↵

- Clark, The Digital Imperative, 28.↵

- Josh Mehler, Stephen McElroy, and Jennifer Wells, “Procedures, Projects, and Programs: Florida State University’s Digital Studio Handbook,” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy 19, no. 2 (2015), http://praxis.technorhetoric.net/tiki-index.php?page=PraxisWiki%3A_%3AProcedures_Projects_Programs.↵

- Sherry Rankins-Robertson et al., “Multimodal Instruction: Pedagogy and Practice for Enhancing Multimodal Composition,” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy 19, no. 1 (2014), http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/19.1/praxis/robertson-et-al/.↵

- Bill Hart-Davidson et al., “Why Teach Digital Writing?” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy 10, no. 1 (2005), http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/10.1/coverweb/wide/.↵

- Walt Whitman, “O Me! O Life!” Walt Whitman: Complete Poetry and Collected Prose, ed. Justin Kaplan (New York: The Library of America, 1982), 410.↵

No comments yet.